Lime; Remembering an Old Friend

Once again, when examining our sustainability choices for buildings, it is instructive to review the architectural legacy left by our ancestors. What works, endures and poses little or no environmental hazards?

In another archive installment, we visited the topic of natural plasters for the interior and exterior of buildings. One ingredient often used in these plasters, or renders, is lime.

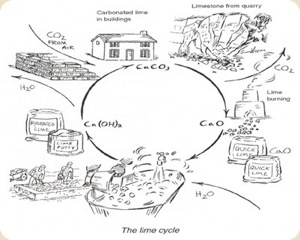

Lime is produced by bringing calcium carbonate (CaCO3 ) in the form of limestone, shells or coral to a high temperature. The heat drives off carbon dioxide (CO2 ) and produces calcium oxide (CaO), or lime, also known as quicklime or lump-lime. The next process required to turn lime into useful building products like mortars, plasters or paints is called slaking. To slake here simply means adding water to the lime and make lime putty or calcium hydroxide

(Ca(OH) 2 ). Left to age, the longer the better, lime putty is then mixed with various components like sand, fiber (straw, saw dust, hair), color pigments, oils and other additives to create plaster, mortar, or paint. Once applied to a building, the lime “product” begins to slowly absorb carbon dioxide from the air (carbonizing) and transform itself back into calcium carbonate (CACO3) or limestone, thereby completing the cycle (see chart).

The resulting finish is hard, weather resistant, inhibits mold and mildew growth and repels insects. Leftover lime products are easily recycled into future uses or put back into the earth without toxic residue. Another noteworthy quality about lime is its ability to “ breathe.” Lime’s vapor permeability is what contributes to the longevity of wonderful historibuildings

around the world. Historic preservationists have learned the hard way that substituting products with lower vapor permeability, like cement based products for instance, has led to failures in the restoration efforts or the building altogether. Lime products are compatible with all earthen and clay- based building methods and highly desirable in a healthy home environment.

The chemical reaction that occurs when lime absorbs carbon dioxide from the atmosphere produces crystals of calcite or calcium carbonate. “These crystals are unusual in that they have a dual refractive index; light entering each crystal is reflected back in duplicate. This results in the wonderful surface glow that is characteristic of limewashed surfaces, and is not found in other decorative finishes. When limewash was discovered, man was not looking for a decorative finish to impress his neighbors. He had actually discovered a sacrificial treatment that protected his dwelling against the worst weather. Early mud structures and wattle and daub (sticks and earth) panels were very vulnerable to the climate and limewash still plays an important part in protecting these surfaces.” (1.)

The use of lime as a primary building material began to wane in 1824 with the patenting of Portland Cement. The use of Portland Cement gained popularity because it is fast setting, hard and “ foolproof—in that any fool can use it, whereas the use of lime requires an understanding of the many processes involved , particularly in the slow carbonation back to limestone in order to use it successfully.” (2.) The decline in lime usage meant a decline in the knowledge of how to use it. Typically, knowledge about lime was passed down from generation to generation and a wealth of experience was preserved.

Thankfully, a renewed interest and appreciation for lime is restoring its rightful place in our building vernacular. Portland Cement still has its place,but we have to come to grips with its high total embodied energy content. It has been said that the manufacture of Portland Cement alone is responsible for approximately 8% of annual greenhouse gas production! Disposal of “used” concrete can be problematic. The low vapor permeability can also be an issue when used incorrectly or with incompatible systems.

The use of lime in not without its challenges, however. While relatively nontoxic, there are some serious safety issues that need to be observed. The first involves the slaking process in that the addition of lime to water should be done carefully as a tremendous amount of heat can produce steam and spit lime. The second safety issue is the fact that lime is so alkaline that it can burn the skin. I have had some lime burns and they are extremely irritating. Protective clothing, gloves and goggles should be worn when working with lime. Portland cement has a lime composition as well and continued exposure to wet concrete can also cause skin irritation.

Proper curing is imperative for lime’s successful use. Freshly applied material should be kept moist by misting for a period of days depending on weather conditions. These surfaces should also be shielded from direct sunlight and high winds during the initial cure time. Success is also measured by the quality of the materials used, the recipes employed and the quality and structural integrity of the surface where the lime material is being applied.

Recipes and advice abound in the natural building and historical preservationist literature. Henry David Thoreau writes about

making quicklime in Walden. I recommend working with someone experienced with lime before using it. At the very least do some solid research and experiment on a small scale before embarking on a major project. The investment in time is well worth the effort. I expect the renewed interest in lime will produce a new generation of skilled and happy craftspeople. Perhaps as we in the Great Lake region are being invaded by Zebra & Quagga Mussels, can develop a way to collect these shells for later burning into quicklime. My appreciation for lime grows daily particularly as I gaze at the lime plastered and limewashed walls in our home. I chuckle to think that our home is turning to limestone! Happy liming!

References:

- The Use of Limewash as a Decorative and Protective Coating; Bennett, Bob; The Building Conservation Directory,U.K. 1997

- Working with Lime (from The Art of Natural Building); Jones, Barbara; New Society Publishers, 2002

- Building with Lime: A Practical Introduction; Holmes, Stafford & Wingate, Michael. Intermediate Technology Publications, 1997

- The Last Straw: The International Journal of Straw Bale and Natural Building. 505-895-5400 or www.strawhomes.com. Issue #29, spring 2000 was dedicated entirely to lime plaster.

- The Straw Bale House. Steen , Athena, Steen, Bill, Bainbridge, David and Eisenberg,David. Chelsea Green Publishing Company, 1994